The country’s banking sector has been experiencing higher outflow than inflow in foreign currency due to repayment pressure of private sector short-term foreign loans when external borrowings of banks declined substantially after Moody’s downgraded the banking system.

This will be a major barrier to rebuilding foreign exchange reserves.

Not only external borrowing, other major indicators of foreign currency inflow including medium-and-long-term foreign loans, net foreign direct investment, foreign aid, and portfolio investment declined significantly intensifying pressure on reserves.

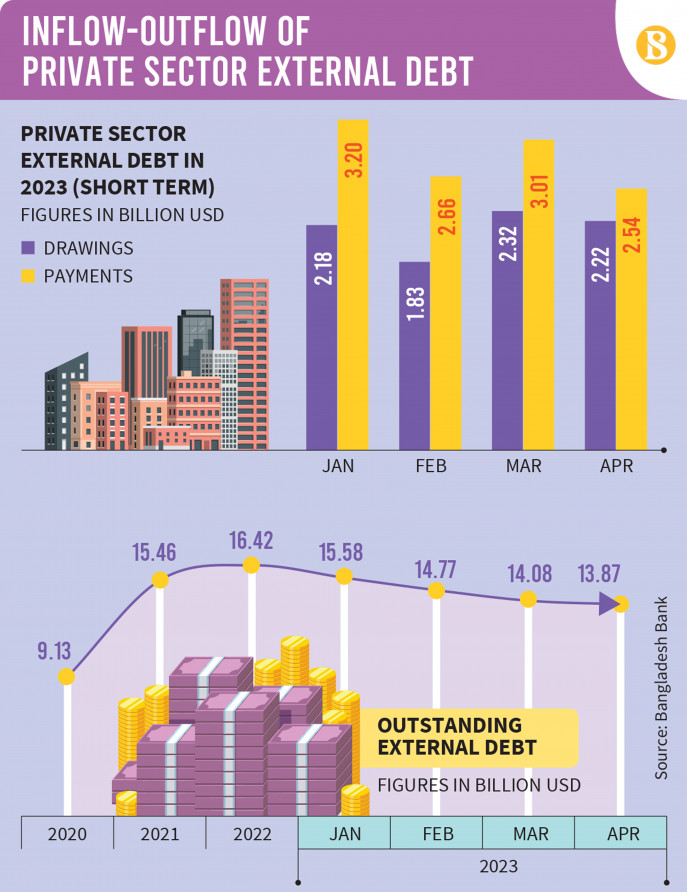

According to Bangladesh Bank data, the repayment amount of the private sector’s external short-term debt stood at $11.40 billion in four months from January to April of 2023, which was nearly $3 billion higher than external borrowings of $8.5 billion.

The total private sector external debt declined by $2.5 billion to $13.87 billion in a span of four months from $16.41 billion in December last year due to higher payments than drawings, central bank data shows.

Private sector businesses and banks borrow from external sources for the highest one year is considered short-term loans. Importers borrow from foreign lenders mostly for purchasing capital machinery which is known as buyer’s credit — when banks take short-term trade loans from foreign sources to settle their external payments.

Short-term loan components include buyer’s credit, deferred payment, back-to-back foreign letters of credit (LCs) and short-term trade loans.

The higher outflow than inflow created a dollar crisis in banks, forcing them to come up with a ruse to delay foreign payments.

Deferred payment, which refers to a temporary postponement of the payment of an outstanding bill, rose to $847 million in April from $689 million at the end of 2022, according to Bangladesh Bank data.

When contacted, a senior executive who heads the foreign trade department of a private commercial bank, told The Business Standard, “Local banks borrow from foreign lenders for short term to settle their foreign payment. However, such external borrowing declined after Moody’s downgrading of the banking system. Foreign lenders are shy to provide loans now.”

On the other hand, foreign borrowing became expensive due to the rise in interest rates. Currently, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) is over 5% and up to 3.5% additional interest adds to this for international loans, which means that borrowers are now subject to pay the highest 8.5% interest on their short-term foreign loans, he said.

The rise in interest rates also increased repayment costs for borrowers. The dollar crisis forced some banks to defer payments which come with higher costs as lenders agree to defer on additional interest charges, he said.

Moreover, import restrictions reduced buyers’ credit which also contributed to a reduction in short-term foreign loan inflow, he said.

Buyer’s credit is a funding mechanism where the buyer of goods borrows from an overseas bank to finance the purchase due to its apparent advantages.

Central bank data shows that the buyer’s credit declined by $1.5 billion to $8 billion in April this year from $9.5 billion in December last year.

Moody’s Investors Service in March downgraded the outlook on Bangladesh’s banking system to negative from stable and in May it downgraded the country’s rating.

Explaining the impact of declining short-term foreign loans, seasoned banker Mohammed Nurul Amin, who served different private banks as managing director, said the decline in buyer’s credit reflects a slowdown in business expansion as 70-80% of imports are raw materials and capital machinery.

Though the reduction of external short-term debt will ease payment pressure in the next two or three quarters, the country’s economy will feel the impact as a fall in capital machinery imports will force many factories to shut causing a rise in unemployment, he said.

Moreover, if businesses go shut, it will hurt export and other foreign currency inflow, eventually putting pressure on reserves, Nurul Amin added.

Other major indicators of foreign currency inflow turn negative

Not only short-term loans, but the inflow of foreign currency from other sources has also been declining, causing continuous erosion in foreign exchange reserves.

For instance, the inflow of medium-and-long-term foreign loans declined by 26.34% to $5.5 billion in the July-April period of the current fiscal year from $7.5 billion in the same period of the last fiscal year, according to Bangladesh Bank data.

Though inflow declined, payment for medium-and-long-term foreign loans increased by 7.40% to $1.3 billion during the same period.

Net foreign investment declined by 12.30% to $1.49 billion in July-April of the current fiscal year from $1.6 billion in the corresponding period of the last fiscal year.

Portfolio investment remained in negative territory for the last year when net foreign aid flows declined by 33% to $4.14 billion in July-April of FY23 from $6.2 billion in the same period of FY22.

Net reserve continues to decline

The Bangladesh Bank could not rebuild its net reserve since February when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) set the condition to improve the net reserve to $24.46 billion by June as part of the condition of getting the second tranche of the $4.7 billion loan package.

The net reserve of the Bangladesh Bank came down to $19.70 billion on 7 June, which was nearly $21 billion in February.

The net reserve will have to be calculated according to the new formula prescribed by the IMF based on the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6).

This net reserve amount is readily available for intervention in the foreign exchange market.

As per the IMF formula, the Bangladesh Bank calculated net reserve for its internal consumption and the figure will be disclosed in the next monetary announcement.

At present, the gross reserve is $29.77 billion. According to the central bank’s new calculation, components that will be deducted from the gross reserve are the FC Clearing Account’s $940 million, Asian Clearing Union’s $670 million (May-June period), $2.03 billion allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDR) at IMF and $350 million Extended Credit Facility at IMF.

Besides, Export Development Fund’s (EDF) $4.50 billion, Green Transformation Fund’s (GTF) $450 million, Long Term Financing Facility’s (LTFF) $750 million, Sonali Bank Financing Facility’s (SBFF) $750 million, Payra Bandar Facility’s $260 million, ITFC’s $230 million deposits and $200 million in advance loan assistance to Sri Lanka also have to be deducted.

A central bank official, wishing not to be named, said it will be difficult to maintain net reserves as per the IMF conditions because the banks are facing a dollar crunch, owing to decreased inflow of remittances and export earnings.

“Besides, the central bank has to sell dollars to pay all kinds of government payments, due to which the reserve is constantly depleting. Besides, there is pressure on private debt repayment which is reducing the foreign currency of the banks,” he said.

The central bank has never had to sell such a huge amount of dollars in the market as it did in the current fiscal year. From July to June of FY 23, it sold about $13 billion to banks.

To compare, it sold only $7.6 billion to the banking system in the previous fiscal year, and the year before the central bank rather bought $6.2 billion from banks.